Photo: Tel Aviv café by Yoav Aziz on Unsplash

MSc Dissertation (Distinction): Creative Class, Active Audience

An early (2014) analysis of symbolic power and cultural labor in digitally mediated urban networks, examining the creative-city paradigm.

NEW MEDIA URBANISM

How Digital Ecologies Recast Urban Identity

At the London School of Economics, I examined how an increasingly digitalized age reshapes the symbolic economy of “creative cities” — urban environments that adopt creativity, cultural production, and aesthetic identity as key engines of economic development (e.g., Tel Aviv, Amsterdam, Berlin).

My MSc dissertation, Creative Class, Active Audience (marked with distinction), draws on months of fieldwork in Tel Aviv to analyze how new media ecologies enable local artists to construct alternative, politically resonant representations of their city — and how these representations intervene in, disrupt, and reconfigure broader struggles over culture, identity, and urban meaning.

Creative Cities, Digital Mediation & Symbolic Economies

Traditionally, urban branding was a top-down enterprise: municipalities, tourism boards, and industry players determined how a city should appear to outsiders and investors. In the era before social media, local artists and grassroots cultural producers were structurally excluded from positions of influence within the city’s symbolic economy.

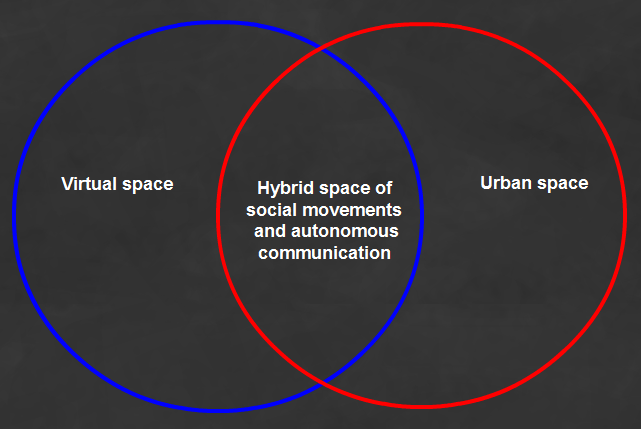

Digital media decisively upended that hierarchy.

Through social platforms, artists — many from minority communities, subcultures, and grassroots social movements — began shaping public perception of the city with unprecedented visibility, volume, and narrative control.

Within this new ecology, these artists form hybrid online/offline communities known as art-world networks (Lesage, 2009): flexible coalitions defined less by institutional gatekeeping than by collaboration, circulation, and identity politics. Their cultural productions — often politically charged and socially situated — now circulate farther and faster than official municipal campaigns.

The result is a profound symbolic inversion:

Digital activity + collaboration

→ increased social capital

→ institutional recognition

→ strategic urban influence

Alternative Representations & Identity Politics

The urban art-world network I embedded with in 2014 articulated a clear, collective aim:

“to represent our city, our way.”

Example of a politically charged public art installation by local artists in a creative city.

Rather than reproducing official imagery — beaches, nightlife, startup culture — these artists spotlighted:

marginal neighborhoods

migrant communities

queer and feminist subcultures

political tensions

everyday life beyond the city’s curated self-presentation

This counter-narrative practice not only diversified Tel Aviv’s symbolic landscape but also exposed the political stakes embedded in aesthetic mediation.

Cultural Heritage, Bauhaus Identity & the ‘White City’

Cultural Heritage Preservation in Tel Aviv (UNESCO World Heritage Site) — Bauhaus International Style — Urban Brand as “White City”.

Tel Aviv’s UNESCO-recognized Bauhaus landscape (the “White City”) plays a central role in its global brand. Artists in the networks I studied often reinterpreted these architectural symbols to critique:

gentrification

erasure of Mizrahi histories

urban inequality

cultural homogeneity embedded in heritage narratives

Their work transformed heritage from a static asset into an actively contested symbolic arena.

Sociopolitical Implications: The Artist as Urban Imagineer

This emerging media environment signals a profound shift in cultural power: urban artists — the so-called creative class — have become “the new urban imagineers,” central actors shaping contemporary symbolic economies and increasingly influencing how cities narrate themselves.

Sir Albert’s Creative Space, Amsterdam: one of many urban creative spaces/think tanks that emerged from the dynamics of new media urbanism. These spaces support artists’ needs for workspace, collaboration, and visibility — and, in turn, contribute to the city’s creative-city brand and economy.

Where urban branding was once a top-down practice dominated by governmental bodies, tourism ministries, and creative-industry intermediaries, the rise of social platforms has inverted the flow of symbolic authority. Today, the cultural productions of local artists routinely outnumber, outrank, and outperform institutional representations in both visibility and public legitimacy. Their work circulates not only as aesthetic expression but as de facto civic commentary, gaining footholds in public discourse “previously inaccessible.”

My findings reveal a consistent pattern:

digital activity + collaboration → increased social capital → institutional recognition.

Artists who participate actively in online networks — especially through shared political commitments, collaborative projects, and mutual amplification — accrue reputational value that establishes them as cultural experts within their cities. These dynamics strengthen their influence across symbolic and bureaucratic systems. Institutions, recognizing this new source of legitimacy, increasingly treat these artists as indispensable partners in urban narrative formation.

Levi, Snir. “‘Creative Class, Active Audience’: How a New Media Environment Informs and Facilitates Identity Politics in Tel Aviv’s Creative Class.” MSc Diss. London School of Economics and Political Science, 2014.

A significant number of artists leverage this heightened visibility to become cultural consultants, municipal collaborators, or full-time contributors within urban institutions. Having effectively entered organizational decision-making structures, they engage in subtle yet consequential forms of symbolic negotiation — advocating for minority perspectives, inserting alternative narratives into official channels, and shaping policy in ways that align with their sociopolitical commitments.

Crucially, these artists remain acutely aware of the risk of co-optation. Many interviewees spoke explicitly about the need to “keep our politics in mind while making decisions,” reflecting a collective understanding that participation within institutions must be balanced with the preservation of subcultural integrity. The tension between influence and autonomy forms a central axis of contemporary creative-city politics.

Analyzing these dynamics contributes to a growing body of work challenging the narrative that the creative class functions merely as a gentrifying or depoliticized force. Instead, the evidence suggests that — under specific urban conditions — creative workers operate as counter-hegemonic agents shaping meaning, civic identity, and symbolic governance.

In more socially oriented creative-city environments (e.g., Amsterdam), these findings underscore the importance of investing in the material conditions, long-term sustainability, and professional opportunity structures available to artists. Such investments not only support cultural and political life but also generate measurable economic benefits in tourism and city branding.

Ultimately, the sociopolitical landscape emerging from new media urbanism demonstrates a new mode of civic participation — one in which cultural producers help construct the frameworks through which cities understand themselves, negotiate identity conflicts, and imagine possible futures.

Economic Implications & Strategic Recommendations

As globalization accelerates and cities compete for attention, investment, and tourism, symbolic distinction becomes an increasingly valuable urban asset. In this landscape, cultural production is no longer supplemental — it is infrastructural. The creative class, once viewed primarily through economic-development metrics, emerges here as a symbolic-economic engine capable of reshaping how cities narrate themselves to both residents and the world.

My research shows that urban artists generate value not only through aesthetic output but through narrative production — the ongoing, distributed work of constructing the city’s meaning. Their images, performances, collaborations, and online circulations articulate a symbolic identity that becomes legible to global publics. As their cultural influence expands, so does their capacity to anchor the city’s brand in authenticity, specificity, and emotional resonance.

Municipalities, tourism ministries, and creative industries thus increasingly recognize that strategic investment in local cultural ecosystems is not merely a cultural good but an economic imperative. Support for artists — through funding, workspace, cross-sector collaboration, and civic partnership — strengthens both cultural life and economic outcomes, particularly in competitive creative-city markets.

Urban stakeholders should therefore consider the following strategic directions:

1. Invest in Creative-City Infrastructure

‘I amsterdam’ — the city’s brand slogan — exemplifies the creative-city paradigm. Its emphasis on individual expression reflects the belief that creativity, innovation, and multicultural density drive economic growth.

Cities with active youth cultures, diverse artistic communities, and dense symbolic life benefit most from adopting aspects of the creative-city paradigm. The key is not aestheticization alone but supporting the conditions under which cultural production can thrive.

This includes:

affordable workspace for artists

long-term funding mechanisms

cross-disciplinary incubators

cultural entrepreneurship support

municipal–artist collaboration programs

These investments amplify symbolic capital and promote sustainable cultural economies.

2. Conduct Deep Ethnographic Inquiry Into the City’s Symbolic Identity

Effective city-branding cannot emerge from generic frameworks.

It requires a grounded understanding of:

Local art-world networks

online/offline community patterns

political and aesthetic sensibilities

cross-artist collaborations

the symbolic vocabulary that defines the city

Urban social movements

core tensions, grievances, and aspirations

minority perspectives

symbolic struggles shaping public space

Youth cultures and subcultures

emergent aesthetic languages

identity politics

grassroots meaning-making infrastructures

These analyses reveal how symbolic meaning is actually produced on the ground — which narratives feel true, which feel imposed, and which resonate across communities.

3. Build Urban-Branding Strategy on Symbolic Authenticity

Cities should avoid branding approaches that overwrite local identity with prepackaged or externally imposed narratives. Instead, they should build strategy from the symbolic material already circulating through daily life.

This means:

partnering authentically with local creators

leveraging grassroots cultural production as brand signal

amplifying emerging aesthetic vocabularies

aligning city messaging with lived experience

Authenticity is not decorative; it is structural.

4. Treat Cultural Producers as Strategic Partners, Not Marketing Tools

The creative class has already become a distributed symbolic force shaping urban identity. Cities benefit when they shift from “using artists” to co-creating with them.

This includes:

involving cultural workers in long-term planning

funding independent cultural platforms

recognizing the political commitments embedded in local art

balancing municipal goals with subcultural autonomy

Such partnerships create durable, nuanced, and resonant symbolic economies.

5. Recognize the Creative Class as a Counter-Hegemonic Resource

Cities facing polarization, identity conflict, or representational fragmentation can draw on local cultural producers as mediators of civic meaning.

Artist networks often articulate alternative imaginaries that:

humanize marginalized communities

push against homogenization

reveal blind spots in policy making

create shared symbolic ground where top-down messaging cannot

This counter-hegemonic function strengthens urban democracy.

Conclusion: Building Cities With Symbolic Intelligence

The dynamics revealed in this research underscore a structural shift:

cities that thrive are those that understand meaning as a form of infrastructure.

By integrating cultural theory, qualitative insight, and symbolic analysis, municipalities can move beyond surface-level branding toward symbolically intelligent urban development — frameworks that honor local culture, support artistic communities, and cultivate economically and emotionally resonant urban identities.

This work demonstrates that new media urbanism is more than a shift in communication.

It is a shift in power, perception, and participation — one that will define the next era of cultural strategy and urban development — a reorientation of who gets to imagine the city, speak for it, and participate in shaping its future.

Levi, Snir. "'Creative Class, Active Audience': How A New Media Environment Informs And Facilitates Identity Politics In Tel Aviv's Creative Class." M.Sc. Diss. London School of Economics and Political Science, 2014. Print.